We have previously examined the life of Fred Korematsu, above, and have seen the degree of his courage in opposing the involuntary internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II. There was yet another individual, Gordon Hirabayashi, who openly defied Order No. 9066 that forcefully relocated so many Japanese-Americans, brutally uprooted them from their lives and livelihoods and for many their property as well.

Hirabayashi was born on April 23, 1918, in Sandpoint, Washington to Shungo and Mitsuko Hirabayashi who emigrated from Nagano Prefecture, Japan – a farming community. Shungo came to the United States in 1907 and was later to marry Mitsuko in 1914. It was an arranged marriage that was not uncommon in that era. Both Shungo and Mitsuko had studied at the Kenshi Gijuku Academy in Japan where they had learned English and eventually converted to the Christian religion. Rather than joining a conventional Christian mainline church they became followers of Kanzo Uchimura (1861 – 1930) who was responsible for founding the Mukyokai movement in Japan. The emphasis of this mode of Christianity proposed a non-liturgical approach to religious practice. It became known for its non-church services.

In 1891, Uchimura gained notoriety when, as a teacher at the First Higher School in Tokyo, he refused to bow before the signature of the emperor affixed to a copy of the new Imperial Rescript on Education. He later changed his mind and from a sickbed sent a colleague to bow for him, but the affair effectually ended his educational career. The Mukoyokai movement was pacifist in its orientation and stressed that behavior should reflect belief. It was apparently this ideology that inspired Hirabyashi to act in a way that lived up to his beliefs.

Once in America, Hirabayashi’s parents were instrumental with others in forming the White River Garden Corporation. In order to accomplish this, the Japanese-American members had to use a white intermediary on account of the fact that the Washington State Constitution had incorporated an alien land law in its founding documents in 1889. In 1921, this law was amended to make it impossible for aliens ineligible for citizenship to hold major shares in a corporation, hold property or hold any major interest in lands delegated for agricultural use. Because of this legal stipulation, the White River Garden Corporation lost its case in the Washington State Supreme Court and the farmland was ceded to the State, but the families involved were allowed to stay on the land and rent it from the State.

Given his unique Christian upbringing, he began to take a pacifist stance in regard to the growing conflict that was embracing Europe and Asia. By 1939 following the German occupation of Poland, the United Kingdom had declared war on Germany. As a consequence of these events, Hirabayashi as a young man registered with the Selective Service as a conscientious objector and joined the Religious Society of Friends, the Quakers, known for their long-standing pacifist theology.

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, it was becoming quite evident that the United States domestic policy had begun to focus on Japanese-Americans as possible being a potential threat to domestic security. Finally, with the promulgation of Executive Order 9066, the military was given the responsibility of implementing the forced migration of Japanese-Americans living on the West Coast to hastily constructed internment camps.

Realizing that his constitutionally mandated rights were being violated, he made the momentous and courageous decision to resist. When the time came requiring him to register for relocation, Hirabayashi turned himself in to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). His strategy was to create a test case as a way to challenge the underlying constitutionality of the federal mandate that ordered the forced incarceration of an entire group without due process of law. He had an underlying faith in the democratic system. He received a substantial amount of legal help and was eventually represented by Frank L. Waters. He was also supported by the American Friends Service Committee and Norman Thomas (1884 – 1968), the noted pacifist and leader of the Socialist Party of the United States for many years.

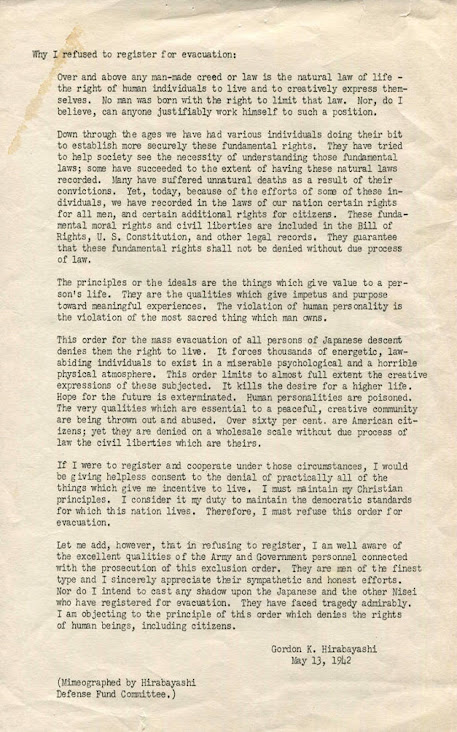

On May 13, 942, Hirabayashi wrote the following letter (see the image below) –

On May 28, 1942, Hirabayashi was indicted for violating Public Law 505 that made the violation of the mandated curfew imposed upon Japanese-Americans a federal crime. He was subsequently arraigned on June 1, 1942, at which time he pleaded not guilty based upon the legal argument that both the exclusion law and the curfew denied him basic constitutional rights as a citizen of the United States.

He ultimately lost this case and was sentenced to serve his allotted time in confinement at a road camp and ended up at a camp outside of Tacoma, Washington. When Hirabayashi’s legal team appealed this conviction to the Supreme Court, Hirabayashi v. United States, the justices by unanimous vote upheld his conviction on June 21, 1943.

He served his remaining time in a prison in Tucson, Arizona. There he met Hopi draft resistors and other pacifists like himself who refused military service on the grounds of being conscientious objectors. This experience reinforced his determination to resist.

Following his release from the federal prison in Tucson, he was faced with yet another challenge to his determination to resist what he believed were unconstitutional infringements on his personal liberty. He received a form from the Selective Service that came to be known as the “loyalty questionnaire (Form 304A). It was entitled, The Statement of United States Citizens of Japanese Ancestry

Since this form specifically singled out citizens of Japanese descent, he refused to fill it out and returned the blank form with a letter detailing his view regarding his view of the legitimacy of the questionnaire. His submission was ignored, and he was subsequently ordered to proceed to the CPS camp for induction. He refused induction. And was charged with Selective Service violations. In court, he represented himself, and was found guilty and was sentenced to one year at the McNeil Island Penitentiary.

After his release and following the end of the war, Hirabayashi completed his studies in sociology and with his advanced PhD degree, he taught abroad in Beirut, Lebanon, Cairo, Egypt, and Alberta Canada where he finally retired in 1983.

Ultimately, his wartime conviction was vacated by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in 1987. This decision represented a repudiation of the extra-legal treatment of the Japanese-American population during the war.

In 1999, Hirabayashi was recognized for his courage and conviction in the face of the assault on his basic freedoms as a citizen of the United States by the renaming of the site of the Tucson Federal Prison in his honor to the Gordon Hirabayashi Recreation Site. In 2002, a kiosk was created that honored not only Hirabayashi, but also the forty-one Nisei draft resistors that were also sent to prison.

Hirabayashi died on January 2, 2012 and was subsequently posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Obama – a fitting acknowledgment to his contributions in living up to a central ideal of democracy – equal treatment of all under the law.